Disability payments held up for some Iraq vets

Jordan Green

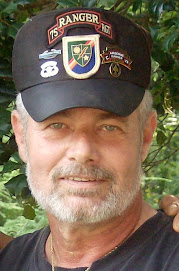

News editor

“The VA told me: ‘Hey, you’re screwed up because of the war,’” retired Army Sgt. Quentin Richardson says. “I didn’t come up with that. It should be automatic. I don’t think there should be any debate about whether or not you should receive the benefits. I didn’t debate serving.”

Quentin Richardson saved the US government $750,000 when he implemented a tracking system to eliminate inefficiencies in the distribution of supplies to detainees at Camp Bucca in southern Iraq. While there, he sacrificed a piece of his sanity when he helped quell a riot of detainees recently relocated from Abu Ghraib, and afterwards carried some of their bodies to the morgue.

In return, the US Department of Veterans Affairs at first insisted that the former National Guard Army sergeant return $17,000 in separation pay received from earlier military service in the Marine Corps before he received disability benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder.

"My life is a nightmare," said the 45-year-old Greensboro veteran, who has not been able to find employment since he returned from Iraq in October 2005. "I was treated better in Iraq than here. I start my day by going to the cabinet to get medication, and I've never been on antidepressants before."

Richardson reenlisted with the National Guard in November 2001, almost a decade after receiving an honorable discharge following the fulfillment of his commitment to the Marine Corps. He deployed as a detainee supply sergeant with the 105th Military Police Battalion in October 2004 to Camp Bucca at Umm Qasr, a port city near the border of Kuwait.

"I decided after 9-11 that I should serve," Richardson said. "I honestly would not have done that if I knew I would have to repay that separation pay, if I knew the battle that I would have to fight with the VA. I left one battleground to return to another."

National advocates say they are seeing a rising number of cases involving Iraq war veterans who incur PTSD and other disabilities after reenlisting, only to find they are unable to receive immediate benefits until they return separation pay.

"This is becoming a widespread problem and the American Legion is concerned because we want to make sure these veterans and service members receive the benefits to which they're entitled," said Peter Gaytan, director of the American Legion's veterans affairs and rehabilitation division. "It's often an extreme hardship for these service members to have to repay prior benefits."

Gaytan said the emergence of complaints by disabled veterans who find their benefits held up because of prior separation pay is so recent that his organization is still struggling to get a handle on how widespread the problem might be.

Coinciding with the increased attention focused on bureaucratic frustration experienced by disabled veterans who have recently returned from combat zones, a new study finds that National Guard members and Army reservists report higher rates of mental health problems than their active-duty counterparts. The study by Army researchers, which was published by the Journal of the American Medical Association three days after Veterans Day, found that difficulties with interpersonal conflict, depression and PTSD increased sharply for all soldiers between the time of their immediate redeployment and later screenings several months into their return to civilian life, with Guard members and reservists reporting consistently higher rates of post-combat difficulties.

"Although rates of PTSD and depression increased substantially between the two assessments, the fourfold increase in concerns about interpersonal conflict highlights the potential impact of this war on family relationships and mirrors findings from prior wars," the study found. The authors wrote that "lack of day-to-day support from war comrades and the added stress of transitioning back to civilian employment" is a unique factor that potentially explains the Guard member and reservists' higher rates of mental health challenges.

Compounding the problem for returning soldiers is a backlog of disability claims at the VA.

"It is an inordinate amount of time that the VA takes to process claims," said William Bradshaw, national service director for Veterans of Foreign Wars. "We are saying that they have a backlog of 800,000 claims. The VA says they have 600,000 claims backlogged. We count appeals and education claims. That's a huge amount of claims that are backlogged."

In Richardson's case, the VA's Winston-Salem regional office informed him in August that he rated as 50 percent disabled as a result of PTSD stemming from the Camp Bucca detainee riot. He was told he would not receive his first disability payment until December 2008 because of the government's recoupment of his separation pay. As explanation for the VA's decision to withhold benefits, the letter stated, "If you are in receipt of separation pay received before October 1, 1996, VA will withhold all the amount the military paid you. After this amount is paid back, you'll start receiving your full VA compensation. "

The Winston-Salem VA acknowledged last week that it had erred in withholding Richardson's disability benefit.

The VA had relied on a provision of federal law that requires veterans who receive disability benefits to return previously received separation pay. The agency overlooked a separate provision that stipulates that separation pay should not be deducted from disability benefits if the separation pay stems from a discharge for an earlier period of service and the disability "is incurred or aggravated during a later period of active duty."

Spokesman Vince Hancock said the VA was redoing Richardson's award and he would likely receive a retroactive payment within 10 days. Hancock said the Winston-Salem VA has a 94 percent accuracy rate, adding that his office would hold a training to remind employees of the provision allowing veterans to receive both separation pay and disability benefits when the payments stem from separate periods of military service.

"I asked, 'Was anybody asleep at the switch?'" Hancock said. "It's not that. We haven't seen a lot of this before. Now, with the global war on terrorism, we are seeing this more often.... It's not unusual that someone would complete a term of service and join the Guard, but prior to the war on terrorism we would often see them perform their reserve duty without being redeployed. Now we're seeing more veterans like Mr. Richardson who reenlist and actually serve in combat."

Danny McDonald, a veteran employment consultant at the NC Employment Security Commission's Greensboro office, said he sees five to 20 veterans a day, about half of whom complain about their benefits being delayed by the VA.

"I really think that it's not fair that you have to wait for your monies after you've put your time in," said McDonald, who is himself a disabled veteran. "When you're in the military, they say, 'Let's get it done, hurry up.' When it comes to us, when we get out they're not hurrying up to give us our benefits.

"I see a lot of stress, whole lot of stress, loneliness, no one to talk to, quick to answer, shy away from a lot of people," McDonald added, "because they're afraid they wouldn't understand."

Richardson said it's hard for him to imagine being employed now; his VA examiner in Winston-Salem noted in July that his PTSD diagnosis indicated that his reliability and productivity were likely reduced and his social functioning moderately impaired. What frightens Richardson the most is his mood swings.

"My wife has tried to understand," he said. "She's gone to counseling sessions. Since the PTSD started she's gone to the vet center. She doesn't like the change in attitude. Sometimes I can catch it. Sometimes I'm just angry. I've changed. I don't sleep anymore. I sleep three or four hours a day [to compensate]. My wife has asked that we resume counseling."

Richardson's service record in Iraq gives the impression of a hard-working and conscientious solider respected by his troops. Today, the soft-voiced veteran presents an image of a meeker version of that. Richardson pursues photography as a hobby, volunteers as a classic-rock DJ at the Guilford College campus radio station, and keeps busy with various projects at the apartment he shares with his wife, who supports the couple on her salary as executive director of the Guilford Community AIDS Partnership.

A narrative for a recommendation for the Bronze Star award describes how Sgt. Richardson coordinated supply operations of consumable and durable goods for a detainee population that expanded from 2,400 to 6,400 in an operation that figured $5.5 million at Camp Bucca. He worked with US contractor Kellogg, Brown and Root and Iraqi vendors.

Richardson's team discovered a circus tent containing more than 2,000 unsecured mattresses at the camp. In addition to stationing a security detail around the mattresses, Richardson assigned his team to unpack them and catalog them. Later, he established an accounting system to track supplies issued to detainees, eliminating the need to rely on the say-so of detainee leaders to gauge the volume of reorders. The Army determined that Richardson's action saved the government $750,000 per year.

The colonel in Baghdad responsible for approving the Bronze Star turned Richardson down for the award, instead issuing him an Army commendation medal.

"Sergeant Richardson is a fine leader respected by his soldiers; he set the example by working hard for long hours with his troops," the narrative states. "He knows his operation and is by far the most knowledgeable person at Camp Bucca in regards to the specific details in managing a Theater Internment Facility supply operation. His actions are in keeping with the finest traditions of military service and reflect distinct credit upon himself, this command and the United States Army."

Following their transfer from Abu Ghraib, detainees - many of them insurgents - revolted at Camp Bucca in January 2005. They set fires, hurled Molotov cocktails and shielded themselves behind mattresses as the US military tried to quell the riot using non-lethal force. When that failed, the soldiers opened fire on the detainees.

"Some detainees lost their lives that day," Richardson said, "I was involved in quelling the riot and I was the person responsible for taking their bodies to the morgue."

Richardson's letter from the Winston-Salem VA confirms Richardson's involvement in putting down the Camp Bucca riot as the combat stressor that likely triggered his PTSD.

"You reported to the examiner that you have been unemployed since leaving the military as you have been unable to obtain a job," the letter states. "You reported panicking during the interview for unknown reasons. You indicated that you have decreased outside social activities, interacting mostly with your wife and child and on occasion outside family or friends."

That Richardson has witnessed death in the combat zone and subsequently received a diagnosis for PTSD hardly makes him unique. The Journal of the American Medical Association study found that more than half of all soldiers who have served in Iraq have witnessed someone being wounded and killed and have themselves felt in danger of being killed. The study found that 40.7 percent of National Guard and Reserve soldiers - twice the rate of their active-duty counterparts - who had been back from Iraq for three to six months had received referrals for mental health concerns or were already under care.

Richardson's VA letter notes that he has experienced ongoing nightmares, flashbacks, exaggerated responses to trauma stimuli, difficulty sleeping at night and concentrating during the daytime, hyper-vigilance and irritability.

"I don't know what went wrong with this war," Richardson said. "I talked to World War II vets yesterday, and they said, 'We had education benefits, we started businesses.' I don't understand it. We don't take care of our veterans anymore."

Richardson is studying political science at Guilford College, and he intends to apply his education to advocacy for returning soldiers who, like him, have run up against hurdles in trying to obtain benefits from the government.

"I'm going to galvanize other veterans," he said. "We're not going to vote for anybody that is not in our interest. I tell young soldiers: 'Vote in '08 because that vote could be a matter of life or death. If we're going to spend upwards of a trillion dollars on this war, then let's spare no cost in taking care of the soldiers."

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment